Frank Medina

Although there were many coaches during the early decades of the twentieth century who also served as “trainers” for the Texas football teams, none advocated weight training for their athletes despite the evidence presented by Roy J. McLean and L. Theo Bellmont. In fact, as Terry Todd documents in his well-researched article, “The History of Strength Training for Athletes at the University of Texas”, UT’s coaches shared the same anti-lifting bias as most other sport coaches in America at the time. Todd wrote in 1993:

But even with such examples as Hammond, plus occasional hints from Bellmont and McLean, the other coaches at U.T. were reluctant to employ weight training as a conditioning aid. So thoroughly convinced were they and their coaching brethren throughout the U.S. that lifting would make a man tight and clumsy that any successes enjoyed by weight trained athletes were summarily dismissed as exceptions which proved the rule. The reasons for this wrongheaded attitude are too complicated to explain in this article, but it was certainly true that throughout the first half of the 20th century, weight training was disapproved of by almost all coaches and physical educators.

...In football, for instance, it was thought almost unmanly to do too much preparation for fall practice. “Hell, fall practice was preparation,” was the way Bully Gilstrap, a former Texas player and coach, put it. Gilstrap is dead now, but he was a football man nearly all his life. He came to U.T. as a freshman in 1920 and he was an outstanding athlete during his college career, lettering in basketball and track as well as in football. He returned to U.T. to coach in 1937 and remained on the staff for 20 years. Gilstrap remembered his playing days.

“Most of the old boys on the team came off the farm like I did and we were in pretty good shape from hauling hay, chopping cotton, cutting wood, and milking, but the only running I did back then was to race somebody or to try and catch one of them old jackrabbits. You got to remember how different things were then. Hell, I won the state track meet running barefoot.

By the time Gilstrap came back to U.T. in 1937, everybody did have shoes, but preseason conditioning for any varsity sport was still almost non-existent. “Things were about the same in ‘37,” he said, “‘cept we had a training table so they wouldn’t none of ‘em have to go through school on chili like I did. But all we did to warm up and all was a few jumping jacks. Then we’d run plays or scrimmage. It was pretty much the same in basketball and track, too. The boys scrimmaged in basketball and they practiced their events in track. That was it. I don’t know what they done in baseball.”

As far as baseball is concerned, the words of the late Bibb Falk are instructive. Falk played at Texas for three years, beginning in 1917, then went straight to the big leagues where he played for 12 seasons. He returned to Austin in 1932, served as assistant coach until 1940, then coached the Texas team until 1968. “We did a little of what we called P.T. in the early days, but only when it rained. Other than that the boys ran and threw and played. We wanted long, loose muscles and the word back then was that lifting would tie you up. To be honest I never even heard of a ballplayer using weights. Not in college and not in the bigs. . . . The key to baseball is power and power comes from speed and we were leery of anything that might slow us up. When I played and for most of my coaching career we always believed that if a man ran enough and threw enough he’d be strong enough.

(To read more click here)

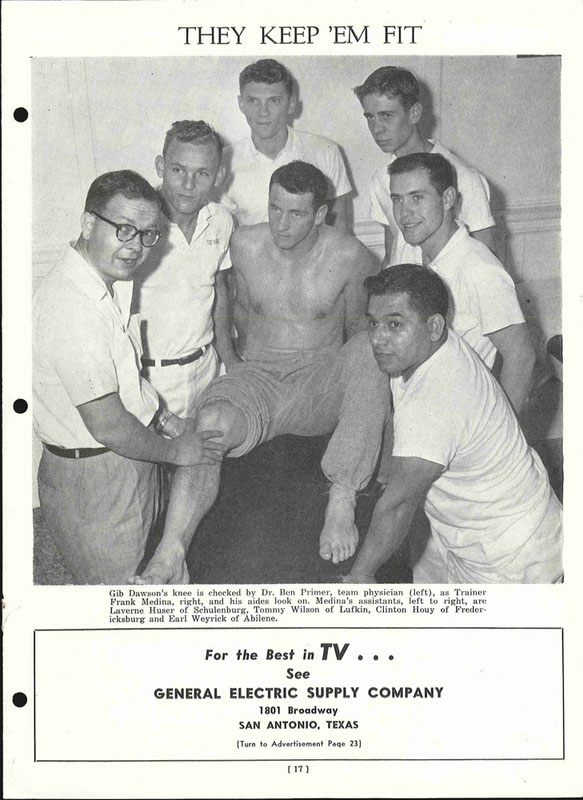

In 1945, the University of Texas hired its first full-time athletic trainer, Nebraska native Frank Medina. The 4’10” Medina would remain in charge of athletic training at Texas for the next 32 years, and he was against the idea of heavy weight training for sport up to his retirement in 1977. As he told Terry Todd, “We never used weights in my early days here because the coaches just didn’t want to. And neither did any other coaches in the country,” he explained. “The coaches here all wanted their players to be quick. And I didn’t believe in it either. I still don’t believe in all that heavy stuff. I always said that if God wanted a boy to be bulgy, He’d have made him bulgy…Some of the football players these days look like weightlifters. That’s not good.”

Although Medina did not recommend heavy lifting, he did finally agree that high repetition work with light dumbbells could be useful. He was inspired by a film he saw about Northwestern University’s training program in the early 1950s, and then told Todd, “A pair of 20 or 25 pound dumbbells is enough for anybody, no matter how big and strong he is,” Medina said. “You need to see how many times a man can lift a light weight, not how much a man can lift once or twice.”

As he told Todd, “After we watched the Northwestern film, one of the things we did before spring training was to have the men wear ankle weights and waist weights and weight vests and lift the dumbbells over their heads while they were jogging around in a heated locker room. I worked them hard.”

Heisman trophy winner Earl Campbell suffered through similarly innervating workouts in the summer of 1977 after new football coach Fred Akers told him to lose 20 pounds before the start of the season. Over that summer, Campbell’s website reports, “Earl met Medina at 6:30 AM, pounding the heavy bag in a rubber sweat suit, running track for an hour, lifting weights and doing 400 sit-ups while wearing a weighted vest. Then it was off to the sauna for over a half-hour. He would attend his classes for a few hours and then participate in practice for the remainder of the evening.” (To read more from Earl Campbell's website, click here)

Although never an advocate for heavy lifting, Medina played an important role in professionalizing the conditioning program for athletes. In addition to starting the first off-season workouts at UT, he also introduced true physical therapy procedures to the UT athletic department. He also brought distinction to the university by serving on two Olympic teams, and he worked with athletes from a wide variety of sports. He passed away in 1989.